“Are you excited?” I wondered why I wasn’t. I should be excited, but that wasn’t exactly how I felt. I was curious. I was eager, interested, I was looking forward to the trip, but I had no concept of what was ahead, so excitement wasn’t quite it.

Three and a half weeks later, heading home, I am filled with many emotions. It has been a time beyond anything I could have anticipated, a time of wonder and possibility, sorrow and joy, beauty and ugliness. My mind has been filled with new ideas. My senses have been overwhelmed. There has been so much to take in. I look forward to being home, and am sad to leave.

Stepping off the small plane, into the embrace of the warm, soft Oaxaca air, we were wrapped in a wonderful scent that came to be my strongest association with this time in Mexico. Partly it’s the smell of earth, but not a musty—more of a dry dusty smell. And it’s the fragrance of wood smoke and charcoal from cooking fires, mixed perhaps with roasting corn tortillas.

In the days following, as we walked around the city, I noticed the aromas of coffee and pastries, wafting from cafés, and less pleasant, but equally strong odors of exhaust, sewage, and fumes. And everywhere, the scent and brilliance of flowers—bursting from every possible crevice or pot, climbing along fences and up walls, shading patios—Bugambilias, Hibiscus, Roses, Lilies, Morning Glories, Sunflowers, Cacti and succulents of all kinds, Eucalyptus and Palms, flowering trees, trees with seedpods resembling long purple Snowpea pods—so many that I don’t know the names of—filling the air with sweetness and almost fluorescent vibrance.

I found myself marveling also at another type of ever-present flower—las Mujeres—especially the indigenous women, who, with their very young children, travel from the pueblos into the city by bus early every morning to sell baskets of goods: handmade crafts, cloth, rugs, bread, as well as cigarettes, candy, and flowers. Wearing ribbons woven into their braids, and vivid floral blouses, they are like blossoms, sudden bursts of dazzling beauty. They, like virtually everyone we encounter, work extremely hard to barely survive.

Contrasts, and sometimes contradictions, are everywhere. The tiny women sitting on the curbs with their baskets of wares, talking on cell phones in their native languages. Art works of incredible beauty and skill stationed next to stalls of the junkiest imported plastic crap. The floral blouses are ubiquitous; some are still sewn and embroidered by hand, some, well, we never got a clear answer, machine-made, perhaps mass produced in sweat shops here, or maybe elsewhere? Gilded churches containing vast plundered wealth, the spoils of looting and exploitation, built literally upon the ruins of Zapotec and other native people’s temples (deliberately ruined by those church-building conquistadores—who then used the very same stones to construct temples to their own deities), whose regal courtyards contain desperate people begging for pennies or food.

On our way from the airport to Al Centro, we pass miles of barrios—tiny wobbly shacks of tin, plywood or even cardboard, jammed together, in congestion like slums of Bombay or favelas of Rio that I’ve only seen in movies. Even these wretched homes have flowers growing in planters made from brightly painted empty laundry detergent containers. And there is street art like I have never seen: every wall is a canvas for a mural, stunning works of skill, to be seen and appreciated—by whom? Perhaps that is not the point.

In the Center all the windows are covered in wrought iron grills, some decorative, some simply functional. On the more trafficky streets, the businesses are poorer with uneven painted lettering. I am surprised and pleased at how many I understand. They remind me of parts of L.A. and I realize the aesthetic has been deliberately imported, with other aspects of culture, from home. I get now why “New” Mexico—like “New England”—is a land reminiscent of home, in which newcomers have re-created the look and feel and sounds of their old world. It feels very familiar—and very new at the same time.

The houses in the city are a mix of old and new. Most are made of plaster over brick or concrete blocks, (reinforced with rebar) usually colorfully painted—a pallet from deep reds and hot pinks to oranges (both terra cotta earth tones and neons) and yellows are the most common, but we see, the rest of the rainbow as well—many green, blue and purple houses.

Just as often, however, are completely raw, unpainted gray concrete, or simple white structures. Roofs are corrugated metal or Spanish tile. The multicolored houses follow the folds of the mountains and from a distance, Rod says, the mountain looks like a skirt, and I think of the colored yokes of the floral blouses.

Everything is warm, even if crumbling too. Up close, some buildings reveal their underlying brick or concrete innards, with piles of “sand” in front on the sidewalks—we watch Leaf Cutter ants in long lines (hormigas cortadoras de hojas) carrying away chunks in their giant pincers to build their own homes. Many outer walls are spray painted with graffiti tags. The houses are built side by side, with shared outer walls and don’t have lawns or front yards—usually a stucco wall or metal gate, often with wrought iron spikes, spirals of razor wire, or “knee scoopers”—shards of glass and broken bottles cemented along the tops facing the street. Inside the gates, again and again we find incredible patios and courtyards, filled with trees, cactuses, flowering vines, iridescent birds and butterflies. It seems that these interior spaces are mostly the places of nature, beauty and tranquility.

At least that’s true in the city. When we travel a mere half hour down the valley to a smallish village, I feel at home. Oaxaca City (and it seems many others in the parts of Mexico we visited) is in a valley ringed by mountains. Actually, it’s on a high plateau of more than 5,000 feet elevation. The Southern Sierra Madres rise another 5—6,000 feet above the valley. Everywhere we traveled in Mexico we saw spectacular mountains. And along the valley floor are remnants of many smaller peaks that look like the conical cores of long ago volcanoes.

Outside the village of Teotitlan de Valle, we climbed one such “Picacho,” which gave us 360 degrees of stunning views. Much of the rock was pumice—stone resembling a sea sponge, filled with holes from evaporating bubbles in the hardening lava of ancient eruptions. We also found many shards of pre-Columbian pottery, which filled me with reverence, feeling the imprints of fingers of people who lived here a thousand or more years ago. A few days later we rode by taxi up into the range high above where we’d climbed, and our Picacho looked like a tiny bump.

In the mountains, I can breathe fully. It is where I feel myself most alive. I am filled with wonder and awe: gigantic Agave cacti open their arms, showing white imprints of ridges on the green skins of the ones within, and shoot stalks with majestic blooms at least twenty feet into the sky, blossoming with the colors of the land—bright yellow, orange and red.

We find Ponderosa Pines and pinecones as large as grapefruits. The taxi driver seems amused but is patient with my request to stop to collect some. We see farms with sheep, cows, goats and chickens, men in wide brimmed straw hats walk behind burros and horses pulling plows and carts along the steep slopes. Harvested corn dries on rooftops. It is though we’ve magically time-traveled back millennia. The air is cold and filled with the fragrance of wood smoke. Why would anyone want to live anywhere else?

Whether in the country or city, everyone seems to do their best to care for their own little spaces. The streets are amazingly clean. (Ironically, the least clean of the places we traveled, was San Miguel de Allende, a city filled with American and Canadian tourists and Ex-Pats.) I was curious about this, not seeing any municipal street cleaning trucks, and gradually realized that each family or business owner, sweeps and washes their piece of sidewalk, mostly they then sweep up their section of the street as well. Amazing. In fact, despite the dust from the arid climate, inevitable city grime, and the concerns about un-potable water, almost everywhere we go is extremely clean.

In contrast to the repetitive narrative of the U.S. state-sponsored media, there is no air of danger such as I often feel in American cities. We, and it seems the entire community, walk along well-lit streets at night, when the city comes alive. The morning, the time I most enjoy walking around, feels quiet and laid back—people setting up their stalls, carrying their wares, chatting, drinking coffee. Afternoon is when the markets begin humming and are active well into evening. The pace feels different too: calm and deliberate, purposeful but relaxed. We get into the habit of having jugo de naranja (fresh squeezed orange juice) in the market every afternoon. It is like Manna—unbelievably delicious. And we find that people are patient and friendly with our awkward attempts to speak in Spanish. They usually don’t laugh, seem to appreciate our efforts to communicate, to learn, and to show respect, though often their English is superior to our Spanish.

Another thing we notice, this one unsettling to us although the Mexicans seem rather unfazed, is lots of Policia with lots of guns—big, automatic machine-gun type guns. Mostly the police are just around—wandering in parks, standing on street corners, sometimes in groups, sometimes individually. I don’t know if it’s the presence of heavily armed people (many police women as well as men), or the normalization of their presence, that is most unnerving.

Despite this reminder of the might of the government, activism seems to be bubbling. In the countryside, a women’s rug weaving cooperative is thriving and has been actively spreading feminist empowerment to the community for 20 years; we encounter groups working to preserve the Zapotec language, environmental conservation efforts, organic farms and markets, nature preserves, and stumble upon an huge march of striking health care workers that brings traffic to a stand-still for an hour. It is gratifying to see the passion and determination these various movements embody. I feel encouraged to try to bring this energy home, hoping, to perhaps make connections among movements.

Another thing that feels like a contradiction to me, as an outsider, are the ongoing Fiestas. It seems that celebration is a semi-permanent state of being. Firecrackers, as well as real fireworks, explode throughout the day and especially during the night. At all hours church bells ring randomly, and at 3:00 a.m. we awake to the sound of a brass band parading through the streets of Teotitlan. What is there to perpetually celebrate? Or is it because life is hard that survival includes creating occasions? I didn’t arrive at a good answer, but did learn to sleep through a lot more than I’d thought possible.

We spent lots and lots of time walking—both in the cities and the rural areas. Quickly the other Gringos were utterly obvious. I was surprised at how conspicuous we are. Even Rod and I are tall in comparison to most Mexicans, and many of the white folks we saw just seemed huge—not something I usually notice in the States. As foreigners, especially as Americans, we’re expected to be wealthy—and ironically, in comparison we are. We benefit from the exchange rate. We benefit from the conditions that keep prices low in Mexico. We benefit from their goods and labor. We might be “helping their economy” by spending money, but it’s an economy that rests on obscene extremes of inequality.

It’s a strange role to find ourselves in. And it creates internal conflict. While most people are working hard or hustling to earn enough to survive, others seem exhausted by the struggle and slump against walls with a can or frail outstretched hand hoping for a few coins. How can we just walk past and ignore them? How can we possibly give enough to make any difference? Why is this horrifying state of existence still possible? When the world has such abundance, and a tiny few people have so much wealth, how can some be reduced to a choice between begging and starvation? How has the world not collectively rebelled against this abhorrent economic system?

Many interactions make me aware of the fortune we have due simply to the accident of birth. Our privilege is due to no great personal qualities, skills or talents of our own; we just happen to have been born into Caucasian, educated, financially stable families. With that accident and that good luck should come responsibility to help others born into more difficult circumstances. Our imperfect temporary personal solution is to carry food with us. Sometimes we place coins into cups, other times we ask, “¿Quiere comida?” and offer a wrapped up burrito or sandwich, usually accepted with surprise and gratitude.

Also heart wrenching are the many homeless, or “peopleless” dogs—intact males, lactating females—living throughout the cities and towns. Some have scarred faces though mostly they look in reasonably good shape, have healthy coats and decent body condition (a few very sad exceptions did not). Many walk stiffly and some limp; I wonder if they’ve been hit by cars. They seem to have their safe places: in parks curled among the roots of large trees, or the within warmth of sandy areas, or in plazas against sunny stone walls. And they seem to travel in family groups. They do not seem afraid of people, but they don’t go out of their way to interact. I assume people offer them food, and sometimes I see them scrounging in the street. I want to take them all home, but as with the desperate people, I wonder what possible difference can I make?

Toward the end of our stay we travel to the Michoacán region, to one of the only twelve peaks in the world where the Monarch butterflies (mariposas) overwinter after their 2,500 mile journey back from North America. The native people of the region consider the butterflies to be their ancestors, returning each year on the Day of the Dead.

I expected to see lots and lots of butterflies; I did not realize that they hung out in pine forests at almost 12,000 feet. We were driven up winding mountain roads to the Reserve (now a UNESCO protected site), then walked (up) from the parking area to where men from the village offer horseback rides (up) the mountain. After a steep trail ride, we dismounted and hiked (up) another several hundred feet elevation gain. Then we entered the world of butterflies.

The day we visited was partly sunny and very chilly. Most of the mariposas were hanging from branches in gigantic clusters (hundreds of thousands of butterflies) bunched together, their wings tightly closed, to stay warm. At first glance, they look like clumps of thousands of pinecones. The ground was also covered in a humming orange and black carpet, butterflies fluttering their wings to generate enough heat to fly back to the safety and warmth of the congregation in the branches. Here, in these few specific mountaintops, they hibernate for winter and begin their journey back in March to reproduce.

It’s a complicated and fascinating migration, gravely threatened by the destruction of open prairie habitat in the U.S. now paved over and built upon, and the eradication of essential milkweed—their source of food and home for their eggs, and by the poisons sprayed on fields throughout Texas and other southern states. It is amazing that they can survive the journey at all, even with optimal conditions. And once again Americans are unthinkingly imperiling an entire Mexican region’s way of life, as well as the existence of these exquisite creatures.

Despite the centuries of imperialism, exploitation, and deliberate destruction of the cultures and people of Mexico—first at the hands of the Spanish “conquerors,” now due to U.S. governmental policies and corporate practices that wring out and appropriate Mexico’s resources—the people we encountered were overwhelmingly welcoming and warm. Of course there were instances where the friendliness faded to disappointment when we declined to buy something being offered, but my deep sense is of a culture much more emotionally open than our own. People generally make eye contact, even with strangers, they say hello and good morning on the street, they are appreciative of service workers like bus drivers and waiters, offering thanks instead of ignoring them or treating them as servants—something we witnessed Americans doing often. This reality is quite a contrast to the stereotype of “murderers and rapists” perpetrated by our shithole president and perpetuated by our popular culture.

Beyond all of the amazing sights and sounds, tastes and smells, food, art, colors, architecture, history, landscapes, and culture, our most profound experiences were moments of human connection. One young man helped us sort through the confusing maze of booking the right connecting bus tickets, only to discover that his internet connection disappeared before the transaction could be completed. He offered to either cancel the transaction or hold the cash in a locked drawer until his computer came back online. (When? Who knows? A sheepish shrug.) Rather than having to start over from scratch, we left the money at the bus station (no receipt), feeling a little uneasy, expecting to walk another 45 minutes back to pick up the tickets later. When we got back to the hotel there was a note that he had phoned, our tickets were booked, and he would bring them to us that evening. He did.

We also met a beautiful, hard-working, young couple who run a little café. They patiently answered all our questions about the proper ways to say things and distinctions in the language that puzzled us. Soon we were laughing together, discussing politics, family, recipes, climate change, and all types of things that friends talk about. Their food was absolutely amazing, and the warmth of their genuine hospitality made us feel truly welcomed. This real, honest, personal connection was for me one of the highlights of the trip.

Despite the daily struggle of their lives, the people seem to have a sense of deep community and caring. As I wondered about that seeming paradox, I also noticed the way children are cherished. In addition to their other bundles, the women usually have a baby or toddler tied to their bosoms or on their backs. First I wondered wouldn’t the babies get squirmy? How can they breathe? But gradually I realized that we’d never heard a peep from them. In fact, during our whole trip, the only children we heard whining, crying or acting out were either North Americans or upper-middle class Mexican tourists. On the seven-hour bus ride from Oaxaca to Mexico City, we sat next to a young mother with a little girl nestled on her lap. The child snuggled in and never complained. We saw many parents playing with children in parks or sitting with them in stalls at market, or lots of other places, and the way they look at their children is a gaze I recognize. It is one of love and tenderness, it says: “You are the most important person in all the world to me.”

Perhaps it is the experience of being deeply loved, and of being in community, that allows people to stay kind and loving despite the hardships of life. Does being in a world of beauty—flowers, artwork, butterflies, and fresh, delicious food—help people experience joy, stay vibrant, creative, connected, and whole? Instead of vilifying our closest neighbors, can we emulate and learn from them something about living fully and about humanity?

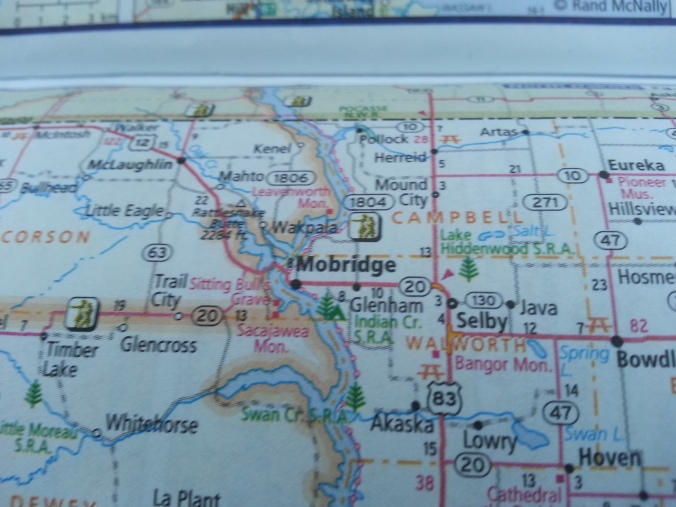

The further north we drive, the more severe the cold and the wind. The sky darkens, and the road is indeed icy and at times covered with drifts. We pass many cars in the gullies perpendicular to the road, some have clearly been there for days judging by the drifts encasing them; one is resting on its roof like an upturned turtle, another faces the road and we can see the smashed front. At Fort Yates we top off our gas tank in case we end up beside the road also. I am stunned by the cold and the wind. I’m from Vermont. I thought I knew winter. This is a different order of magnitude. Iowa and South Dakota were windy but when we get out at the gas station, the cold rips through me; this new wind is intense. We put on even more layers and keep going, slowly and steadily into the worsening weather.

The further north we drive, the more severe the cold and the wind. The sky darkens, and the road is indeed icy and at times covered with drifts. We pass many cars in the gullies perpendicular to the road, some have clearly been there for days judging by the drifts encasing them; one is resting on its roof like an upturned turtle, another faces the road and we can see the smashed front. At Fort Yates we top off our gas tank in case we end up beside the road also. I am stunned by the cold and the wind. I’m from Vermont. I thought I knew winter. This is a different order of magnitude. Iowa and South Dakota were windy but when we get out at the gas station, the cold rips through me; this new wind is intense. We put on even more layers and keep going, slowly and steadily into the worsening weather.

We bring snack stuff to the Mess Tent where a young woman is describing all the menu choices (including vegan options) and serving from big pots and trays cafeteria style. We stop for a few moments to devour some squash soup which is the best squash soup ever, despite the little hard chunks of something I can’t identify and keep picking out.

We bring snack stuff to the Mess Tent where a young woman is describing all the menu choices (including vegan options) and serving from big pots and trays cafeteria style. We stop for a few moments to devour some squash soup which is the best squash soup ever, despite the little hard chunks of something I can’t identify and keep picking out. I also realize that the sheds we’ve been walking past, where people are sitting behind a plywood wind break, and announcements are being made, is actually the Sacred Fire. Somehow I hadn’t imagined the Sacred Fire to be so small or right in the hustle and bustle of the camp, but then I notice that people are sitting near it, praying quietly. I pull my long skirt out of my bag and slip it on over my snow pants, as requested on the Oceti Sakowin website as a sign of respect. I’d brought it a bit reluctantly, resistant (as I’ve been my whole life) to being instructed to dress according to a code. But wearing it is transformative. Suddenly I feel no longer an outsider, I feel as if I belong.

I also realize that the sheds we’ve been walking past, where people are sitting behind a plywood wind break, and announcements are being made, is actually the Sacred Fire. Somehow I hadn’t imagined the Sacred Fire to be so small or right in the hustle and bustle of the camp, but then I notice that people are sitting near it, praying quietly. I pull my long skirt out of my bag and slip it on over my snow pants, as requested on the Oceti Sakowin website as a sign of respect. I’d brought it a bit reluctantly, resistant (as I’ve been my whole life) to being instructed to dress according to a code. But wearing it is transformative. Suddenly I feel no longer an outsider, I feel as if I belong.